Kelly, I think your post provokes some interesting questions for discussion tomorrow. First, it would be productive to focus on the form and genre. Mallory already mentioned the fragmentation and stream-of-consciousness effect in Zograf's comics. We are not getting a "realistic" narrative here, but rather a collection of thoughts, dreams, fragments of everyday life. Moreover, Zograf's drawing style is rather unique, surrealistic, playful, ironic, and at times very stark and "Kafkaesque," to use a literary analogy. He mobilizes pop culture and subculture references to estrange the Western reader/viewer who comes to this text with certain expectations and prejudices about the "the Balkans", "the Serbs" etc. For stylistic comparison, see R. Crumb and some other underground comic artists, such as Art Spiegelman, Chris Ware. This is definitely strategic on Zograf's part; but it is also part of his artistic genealogy, in the same way Shklovsky, Nabokov, and Brodsky are appropriated and quoted by Ugrešić in

The Museum of Unconditional Surrender.

For example, Zograf comments on his form and genre explicitly in one of the comics: "...my stuff is not strictly 'documentary' ... it is some kind of fantastic realism, in a good Russian tradition... I think that the whole situation could be properly described by pointing at some peripheral details... in our life, we are always watching just fragments ... we have to use our imagination if we want to grasp the whole picture..." (54)

There's plenty of stuff to discuss in this one quote. How does Zograf achieve the documentary effect? I would argue in several ways: by indexing specific dates and using the explicitly autobiographical diary genre, by inserting fragments of "reality" (the dinar bills, NATO propaganda leaflets) etc. We saw this in other texts as well. We can also discuss the use of marginalia..."the peripheral details" which, as Zograf argues, can be more revealing than master narratives (compare to Jameson, who laments the grand narrative of History in postmodern age). What about the use of fantasy, dreams, urban legend and folklore? To what extent is popular culture a site of resistance, both against the ruling authoritarian regimes in the ex-Yugoslavia (which is also appropriating popular culture and folklore, think of Ugresic's

Culture of Lies) and against neo-colonial dehumanization of peoples outside of the "West"?

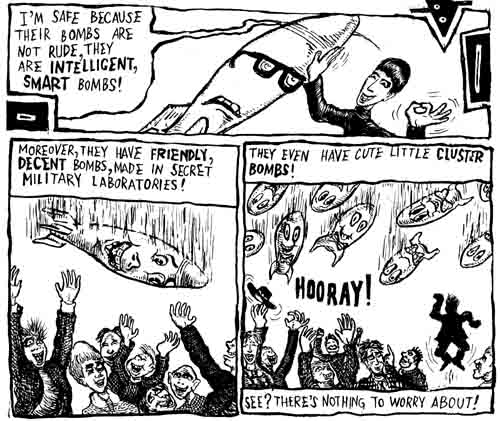

This also feeds into Kelly's post about the power of images. I think there are few things we can discuss here. First, the fact of postmodern warfare. What I have in mind here is the appearance of "imbedded" reporting, and televised images that shape our perception of the "enemy" on the ground, which is additionally connected to the whole mass media/military apparatus. It has become apparent that in such "humanitarian" interventions, "preemptive" wars, and wars against terrorism--such as the NATO bombing of Serbia, Kosovo (in the former category) and the war in Iraq and Afghanistan (in the latter)--the line between civilians, soldiers, and "enemy combatants" is very blurry, to say the least. Not to mention the line between civilian, military, and industrial infrastructure subjected to bombing. And since Western countries have vested interest in decreasing the number of domestic casualties, most of these wars have been waged from the air, or more recently, by combat drones (

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/20/world/asia/20drones.html). Moreover, the media will often uncritically use the same terms as the military and the government to describe the situation. I have already mentioned some terms that have invaded our language about war: "humanitarian intervention", "preemptive strike", "shock and awe", "enemy combatant", "homeland security" etc. etc. All of this, I would argue, has changed our perception of war and its horrors, as well as the ways in which war is viewed, discussed, remembered or, more likely, forgotten. The fact is that we encounter these images most often out of context, disconnected from narratives of people on the ground. Since we have people to think strategically and technically about our wars, we, the citizens of countries involved in these wars, somehow don't have to think about it, (although we will have to pay for it in the long run).

|

| "Shock and Awe" |

I agree with Kelly that images of horror are much less effective at times than pictures of people in wartime trying to maintain a sense of normalcy, dignity, or just trying to survive. After all, we live in an age (perhaps we've always lived in such an age) where representations of horror and violence--and shock in general--have become a mundane aesthetic experiences. Any thoughts?

To return to Zograf, I want us to briefly discuss the representation of the Serbian other, the Kosovo Albanians in this case. In what way does Zograf make room in his comics for the plight of Kosovo Albanians? How does his marginal position enable him to stay critical of the Milošević regime and at the same time condemn the NATO bombing? And to include the point of view of the other? Were you satisfied with this representation? I think this is important to discuss since many of the cultural ties between Kosovo Albanians and Serbs have been severed and revanchist feelings on both sides still haven't subdued, not only because of the fresh war traumas but also the ongoing territorial disputes, questions of sovereignty. Recently, the younger generation of Serbian and Kosovo writers have been trying to reestablish connections by translating short stories, which I see as a positive, if not a radical move towards some sort of dialogue and understanding of the trauma of the other:

http://www.seecult.org/vest/iz-beograda-s-ljubavlju-na-albanskom (text in BCS).

As Arendt has argued, birth--broadly considered--represents one of the most monumental political events, the fact that space is made in the world for a new, unique individual, or collectively speaking, a new generation of people. What we are seeing in the Balkans--and elsewhere--is that nationalistic war and authoritarian rule have deprived a whole generation of people of their future. Now they're trying to regain it, even though they are inevitably stuck with the traumas, guilt, and burdens of the previous generation which they must confront whether they like it or not.

Here is a more recent comic by Zograf on this theme (part of his weekly contribution to the Serbian magazine,

Vreme; translation follows) :

|

| The Horror of Growing Up: Cap1: "As mature persons, it is hard for us to understand why during our early childhood the universe sometimes brought us to tears... What was the reason for this infantile pain in the face of our existence? I thought about this while sorting through photographs which I acquired at the flea-market..." Cap 2: "In fact, it is perhaps understandable that the gentle soul of a child will be surprised when faced with the circumstances that govern physical reality. It can be a real challenge if--let's say--you were destined to grow up among moustachioed Montenegrins, some of which may even be armed." |

|

| Cap3 : "In the end, you somehow come to the conclusion that it is completely natural for a youngster to be spellbound when confronted with a world that is about to plop down on your feeble shoulders... Maybe we would bawl even more and even louder, if we only knew that we'd grow into all those boring, "serious" people..." |